Introduction

"George Washington lived sixty-seven years, from 1732 to 1799. During his last twenty-four years—more than a third of his life—he was the foremost man in America, the man on whom the fate of his country depended more than on any other man.

And these were fateful years. From 1775 to 1783—the years of the American War of Independence—Washington was Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army upon whose victory the thirteen colonies depended to secure their separate and equal station among the powers of the earth. In the summer of 1787, he presided over America's Constitutional Convention. His presence lent decisive significance to the document drafted there, which continues in force in the twenty-first century as the oldest written constitution in the world. From 1789-1796, he held the highest office in the land as the first president of the United States of America under this constitution. The office of president had in fact been designed with his virtues in mind.

In each of these capacities, and as a private citizen between and after his several public offices, Washington, more than any American contemporary, was the necessary condition, the sine qua non, of the independence and enduring union of the American states. It was in mere honest recognition of this that time bestowed upon him the epithet, Father of our Country, and that upon his death, the memorial address presented on behalf of the Congress of the United States named him "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen."

The pre-eminent positions that he held, the unrivalled honors he received, can only hint at the greatness of Washington. They are rays cast by the light of his greatness itself, the qualities of mind and character that shone brilliantly in all these positions and fully deserved all these honors—and more. The three sections here introduce readers to Washington's greatness, call attention to some of his most striking qualities of mind and character, and suggest the significance of this great man for our generation, and for every generation, of Americans.

George Washington and our World

Why should young Americans who care about their country and aspire to do something worthwhile with their lives be interested in the greatness of George Washington? For at least two reasons: First, although knowing what is worthwhile and what is possible is essential to living a good life and doing some good for our country, we are not born knowing these things.

We learn these things in three ways: by experience, reflection, and study. If we are fortunate, our family and our friends provide us with examples of what is worthwhile, what is good. A hard-working father, a wise and loving mother, a friend who stands up for us in a pinch teaches us by his example. Knowing them--experiencing their goodness and reflecting upon it--is one of our most important educations. It introduces us to both what is good and what is possible, and it inspires us to be like those we love and admire.

Greatness, however, is by definition extraordinary, and what is extraordinary is by definition rare. It takes nothing away from parents or friends to say that most of us do not know personally someone with truly extraordinary gifts or capacities. And yet, it is extraordinary qualities that most clearly reveal what is good--what is the standard of excellence in any field--by revealing more clearly the limits of what is possible. We see more clearly what baseball is, so to speak, when we see Babe Ruth swing the bat... After seeing him play--after studying him--those of us who play the game know better what to aspire to and the rest of us understand more fully the highest standards by which the game should be judged.

Like Babe Ruth..., a Socrates, a Shakespeare, a Mozart, displays qualities or capacities that would have been difficult or impossible to imagine without his example. In this way, those with the greatest gifts reveal to the rest of us—they make visible—human potential that we might otherwise never have realized on our own. This means that they help reveal to us human nature itself, since we cannot understand human nature until we have some idea what human beings are capable of.

What Shakespeare is to poetry, Mozart to music, or Babe Ruth to baseball, George Washington is to life itself. He possessed and displayed in his life courage, self-control, justice, judgment and an array of other virtues in such full harmony and to such a degree, and he surmounted such great challenges in so many circumstances of war and peace, that to see how he lived his life is to see much more vividly what it means to be a man. This is by no means to say that he was flawless any more than Babe Ruth was a perfect baseball player. It is merely to say that, if he had not lived, such greatness could hardly have been believed possible.

This, then, is the first reason to be interested in the greatness of Washington.

The second reason has particularly to do with America. In the course of his life, Washington’s fate became inseparable from the fate of his country. By the time of his death he was identified in the eyes of the world with America and the cause of liberty for which America stood. His greatness was a testament to America’s promise. The significance of that testament has not diminished with time. To the contrary, for anyone who wants to understand this country and help fulfill its promise, it is, if anything, more necessary today than at any time in the past to understand the greatness of George Washington. It is still true, 200 years after it was first said by Fisher Ames in a eulogy of Washington, that "Our history is but a transcript of his claims on our gratitude."

George Washington and His World

When Washington was a mere twenty-two years old, he had already been appointed commander of the armies of Virginia (such as they were). His actions in the field had already won him notoriety in Europe and fame in Virginia. By the time he retired from military service at the age of twenty-six and returned to private life, his commanding presence, courage, resolution, incorruptible justice, and firm sense of duty were widely known throughout Virginia. Already, his destiny seemed to fellow citizens to be tied to the destiny of his "country" (that is, Virginia).

Twenty-seven of the officers who served under the young Washington presented an Address to him (December 31, 1758) upon his retirement, expressing their gratitude for his leadership and imploring him not to resign. Their youthful tribute to the youthful Washington anticipates the man whose destiny would become inseparable from the destiny of a greater country, when it called him from his private station some seventeen years later.

"In our earliest infancy, you took us under your tuition, trained us up in the practice of that discipline which alone can constitute good troops . . . . Your steady adherence to impartial justice, your quick discernment and invariable regard to merit, wisely intended to inculcate those genuine sentiments of true honor and passion for glory, . . . first heightened our natural emulation and our desire to excel. How much we improved by those regulations and your own example, with what cheerfulness we have encountered the several toils, especially while under your particular direction, we submit to yourself . . . . Judge then how sensibly we must be affected with the loss of such an excellent commander, . . . How great the loss of such a man? . . . It gives us additional sorrow, when we reflect, to find our unhappy country will receive a loss no less irreparable than ourselves. Where will it meet a man . . . so able to support the military character of Virginia? . . . In you we place the most implicit confidence. Your presence only will cause a steady firmness and vigor to actuate in every breast, despising the greatest dangers and thinking light of toils and hardships, while led on by the man we know and love."[1]

Such were the impressions and the sentiments of men who knew and served under Washington in his early twenties.

When George Washington died, on December 14, 1799, there was throughout America a profound outpouring of grief at our loss, gratitude for his life, and deep reverence for his memory. "For two months after Washington’s burial at Mount Vernon, his countrymen continuously expressed their bereavement in private correspondence, in resolutions of Congress and of State legislatures, in town meetings, in the pages of newspapers and, most singularly, in hundreds of funeral processions and solemn eulogies in every corner of the nation."[2] America’s greatest orators vied with one another to do justice to the greatness of this great man.

From the Senate of the United States: "With patriotic pride, we review the life of our Washington, and compare him with those of other countries who have been pre-eminent in fame. Ancient and modern names are diminished before him. Greatness and guilt have too often been allied, but his fame is whiter than it is brilliant. . . . Let his countrymen consecrate the memory of the heroic General Washington, the patriotic statesman and the virtuous sage. Let them teach their children never to forget that the fruit of his labors and his example are their inheritance."[3]

Congressman Henry Lee, on behalf of the House of Representatives: "First in war--first in peace--and first in the hearts of his countrymen, he was second to none in the humble and endearing scenes of private life; pious, just, humane, temperate and sincere; uniform, dignified and commanding; his example was as edifying to all around him as were the effects of that example lasting. . . . [C]orrect throughout, vice shuddered in his presence and virtue always felt his fostering hand; the purity of his private character gave effulgence to his [public] virtues. . . . Such was the man for whom our nation mourns."[4]

Nor were the memorials confined within American shores. "The whole range of history," wrote the editor of the Morning Chronicle in London, "does not present to our view a character upon which we can dwell with such entire and unmixed admiration. The long life of General Washington is not stained by a single blot. . . . His fame, bounded by no country, will be confined to no age."[5] Even Napoleon delivered a public eulogy of Washington at the Temple of Mars and ordered ten days of national mourning in France.

Abigail Adams was right in saying: "Simple truth is his best, his greatest eulogy. She alone can render his fame immortal."[6]

George Washington the Man

Countless witnesses attest that, however astonishing Washington’s many particular qualities of mind and character might be, the sum was even greater than the parts: The whole man somehow magnified the individual virtues of which he was composed. His courage, energy, high principles, and steadfastness; his impartial justice and utter trustworthiness; that he was calm in the face of danger and dauntless in adversity; that he would sacrifice repose for fame and fame to duty; his thoroughness in deliberation and mastery over his strong passions—these and his other distinguishing characteristics, laudable in themselves, are elevated still further as they are harmonized in the mind and character of Washington."

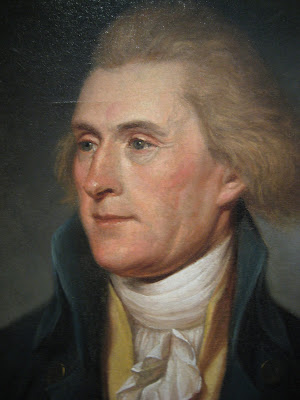

The verbal portrait of Washington that follows draws together several of the most widely noted qualities of Washington’s mind and character into a picture of the man himself as he acted on the stage of America’s destiny (from a private letter by a Virginia Republican—Thomas Jefferson).

Thomas Jefferson remembered Washington fourteen years after his death, in a letter of January 2, 1814, to Dr. Walter Jones.[7]

". . . I think I knew General Washington intimately and thoroughly; and were I called on to delineate his character, it should be in terms like these.

"His mind was great and powerful, without being of the very first order; his penetration strong, though, not so acute as that of a Newton, Bacon, or Locke; and as far as he saw, no judgment was ever sounder. It was slow in operation, being little aided by invention or imagination, but sure in conclusion. Hence the common remark of his officers, of the advantage he derived from councils of war, where hearing all suggestions, he selected whatever was best; and certainly no General ever planned his battles more judiciously. But if deranged during the course of the action, if any member of his plan was dislocated by sudden circumstance, he was slow in re-adjustment. The consequence was, that he often failed in the field, and rarely against an enemy in station, as at Boston and York. He was incapable of fear, meeting personal dangers with the calmest unconcern. Perhaps the strongest feature in his character was prudence, never acting until every circumstance, every consideration, was maturely weighed; refraining if he saw a doubt, but, when once decided, going through with his purpose, whatever obstacles opposed. His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known, no motives of interest or consanguinity, of friendship or hatred, being able to bias his decision. He was, indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good, and a great man. His temper was naturally high toned; but reflection and resolution had obtained a firm and habitual ascendancy over it. If ever, however, it broke its bonds, he was most tremendous in his wrath. In his expenses he was honorable, but exact; liberal in contributions to whatever promised utility; but frowning and unyielding on all visionary projects and all unworthy calls on his charity. His heart was not warm in its affections; but he exactly calculated every man’s value, and gave him a solid esteem proportioned to it. His person, you know, was fine, his stature exactly what one would wish, his deportment easy, erect and noble; the best horseman of his age, and the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback. . . .

"

On the whole, his character was, in its mass, perfect, in nothing bad, in few points indifferent; and it may truly be said, that never did nature and fortune combine more perfectly to make a man great, and to place him in the same constellation with whatever worthies have merited from man an everlasting remembrance. For his was the singular destiny and merit, of leading the armies of his country successfully through an arduous war, for the establishment of its independence; of conducting its councils through the birth of a government, new in its forms and principles, until it had settled down into a quiet and orderly train; and of scrupulously obeying the laws through the whole of his career, civil and military, of which the history of the world furnishes no other example...

"

These are my opinions of General Washington, which I would vouch at the judgment seat of God, having been formed on an acquaintance of thirty years. . . .

"

I felt on his death, with my countrymen, that ‘verily a great man hath fallen this day in Israel.’"

____________________________________________

Source: The Claremont Institute (originally published on PBS) - no longer available online.

For further reading see: Brookhiser, Richard, Founding Father: Rediscovering George Washington (Free Press, 1997) https://www.amazon.com/Founding-Father-Rediscovering-George-Washington/dp/0684831422

Footnotes:

[1] James Thomas Flexner, George Washington: The Forge of Experience (1732-1775) (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1965), 222. Douglas Southall Freeman, George Washington: A Biography, Volume Two (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948), 380-381.

[2] John Alexander Carroll and Mary Wells Ashworth, George Washington, Volume seven: First in Peace (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1957), 648.

[3] Albert Bushnell Hart, ed., Tributes to Washington, Pamphlet No. 3 (Washington, D.C.: George Washington Bicentennial Commission, 1931), 21.

[4] The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States. Sixth Congress (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1851), 1310-1311.

[5] John Alexander Carroll and Mary Wells Ashworth, George Washington, Volume seven: First in Peace (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1957), 648.

[6] John Alexander Carroll and Mary Wells Ashworth, George Washington, Volume seven: First in Peace (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1957), 653.

[7] Thomas Jefferson, Writings, ed. Merrill Peterson (New York: The Library of America, 1984), 1318-1321.