By Tony Williams

On

January 27, 1838, a young Abraham Lincoln addressed a Young Men’s Lyceum

debating club in Springfield. The

topic of the speech was “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions” and

addressed the tumult in American society raised by radical abolitionism who

were willing to sacrifice the laws to the “higher law” of justice for slaves. The address, however, raised

fundamental questions about human nature, the authority of law, and the

American founding. Lincoln’s

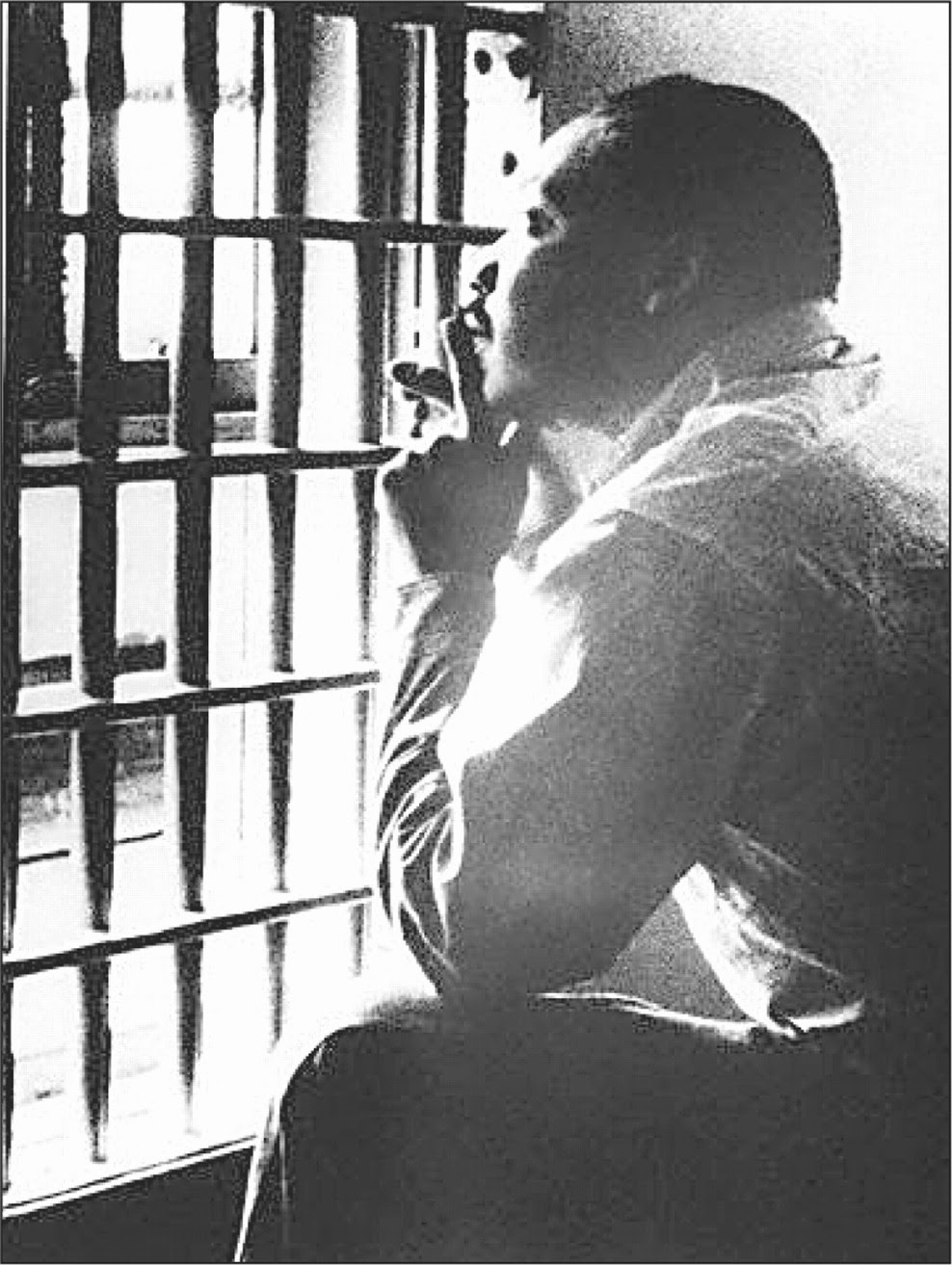

speech raises an interesting counterpoint to Martin Luther King’s “Letter from

Birmingham Jail” which I wrote about on the WJMI recently.

Lincoln

begins the speech by expressing reverence for the American political tradition

of self-government which was more conducive to “the ends of civil and religious

liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us.”[i] The Founders left a legacy that was

“hardy, brave, and patriotic” to the present generation. They inherited that gift of republican

self-government and had a grace responsibility to transmit it to their

posterity: “This task gratitude to our fathers, justice to ourselves, duty to

posterity, and love for our species in general, all imperatively require us

faithfully to perform.”

The

greatest threat to ensuring the survival of that inheritance was not from

outside enemies but from the suicide of a nation of free men who lived by

license rather than ordered liberty.

“I mean the increasing disregard for law which pervades the country; the

growing disposition to substitute the wild and furious passions, in lieu of the

sober judgment of Courts; and the worse than savage mobs, for the executive

ministers of justice.”

Lincoln

is assuming a classical and Christian position in which man is a rational being

who can master his passions and become a self-governing individual. In Book IV of The

Republic, Plato has Socrates explain that, “Moderation is surely a kind of

order and mastery of certain kinds of pleasures and desires, as men say when

they use . . . the phrase ‘stronger than himself.’”[ii] In second book of the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle tells us

that, “Virtue, then, is a state of character concerned with choice, lying in a mean

. . . this being determined by a rational principle” over irrational passions

and desires.[iii] St. Paul tells us in Romans 6:12, “Therefore do not let sin

reign in your mortal body so that you obey its lusts.” These thinkers agree with Lincoln that

rational man can gain self-mastery by controlling his passions through

reason.

Many

Founders adopted this classical and Christian stance on human nature such as

James Madison when he wrote about the danger of factions in The Federalist. In

Federalist #10, Madison wrote, “By a faction I understand a number of

citizens, whether amounting to a majority or minority of the whole, who are

united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse

to the right of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of

the community.”[iv]

For

Lincoln, moral license leads to vice, violence begets violence, and unpunished

acts spawn a lawless spirit among the American people. Soon, both the guilty and innocent

“fall victims to the ravages of mob law . . . till all the walls erected for

the defence of the persons and property of individuals are trodden down, and

disregarded.” The result is

ultimately that the “strongest bulwark of any Government, and particularly of

those constituted like ours, may effectually be broken down and destroyed – I

mean the attachment of the

People.”

Lincoln’s

answer to the destruction of law and liberty in the land is poetic, reasonable,

and practical:

Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher

to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the

least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their

violation by others. As the

patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence,

so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his

life, his property, and his sacred honor; - let everyman remember that to

violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the

character of his own, and his children’s liberty. Let reverence for the laws, be breathed by every American

mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap – let it be taught in

schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in Primers, spelling

books, and in Almanacs; - let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in

legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation.

Lincoln

wants to build laws rooted in reason to frustrate the designs of ambition of a

Caesar or Napoleon, and to foil the passions of a mob. He admits near the end of the speech

that the passionate mobs of the American Revolution were dedicated to liberty

and threw off British rule to advance the “noblest cause – that of establishing

and maintaining civil and religious liberty.”

However,

the Founders had passed away, and a new generation has been given the reins of

self-government. Lincoln finishes

with another poetic appeal to reason, law, and the name of Washington:

That temple must fall, unless we, their descendents, supply

their places with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober

reason. Passion has helped us; but

can do so no more. It will in

future be our enemy. Reason, cold,

calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our

future support and defence, - Let those materials be molded into general intelligence, sound morality, and in particular, a reverence for the constitution and laws:

and, that we improved to the last; that we remained free to the last; that we

revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no

hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which

to learn the last trump shall awaken our WASHINGTON. Upon these let the proud fabric of freedom rest, as the rock

of its basis; and as has been said of the only greater institution, “the gates of hell shall not prevail against

it.”

That same

burden to preserve the laws, the Constitution, and American principles of

religious and civil liberty binds us.

May we do so through well-reasoned, civil discourse rather than partisan

demagoguery.

Tony Williams is the Program Director of the WJMI and the

author of America’s Beginnings: The Dramatic

Events that Shaped a Nation’s Character.

[i] All quotes from Lincoln’s speech can be

found in Roy P. Basler, ed., Abraham

Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings (New York: Da Capo, 2001), 76-85.

[ii] Allan Bloom, The Republic of Plato (New York: Basic Books, 1968), 109.

[iii] Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980),

39.

[iv] Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and

John Jay, The Federalist Papers, ed.,

Clinton Rossiter (New York: Signet, 1961), 72.