By: Tony Williams

Most

everyone knows Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, which I wrote

about here on its fiftieth anniversary last August. The March on Washington and King’s famous speech had a

singular impact upon the Civil Rights Movement and passage of the Civil Rights

Act. The “I Have a Dream” speech

was profoundly shaped by American founding constitutional principles.

As

important and brilliant as the “I Have a Dream” speech was, the lesser-known

“Letter from Birmingham Jail” was perhaps an even more profound examination of

the principles of constitutionalism and justice.

In

early 1963, King and the movement were faltering after a failed campaign in

Albany, GA, to raise awareness of the injustice of segregation. The leaders of the movement decided

strategically to make Birmingham, AL, a showcase of injustice with the reaction

of a virulently racist police chief.

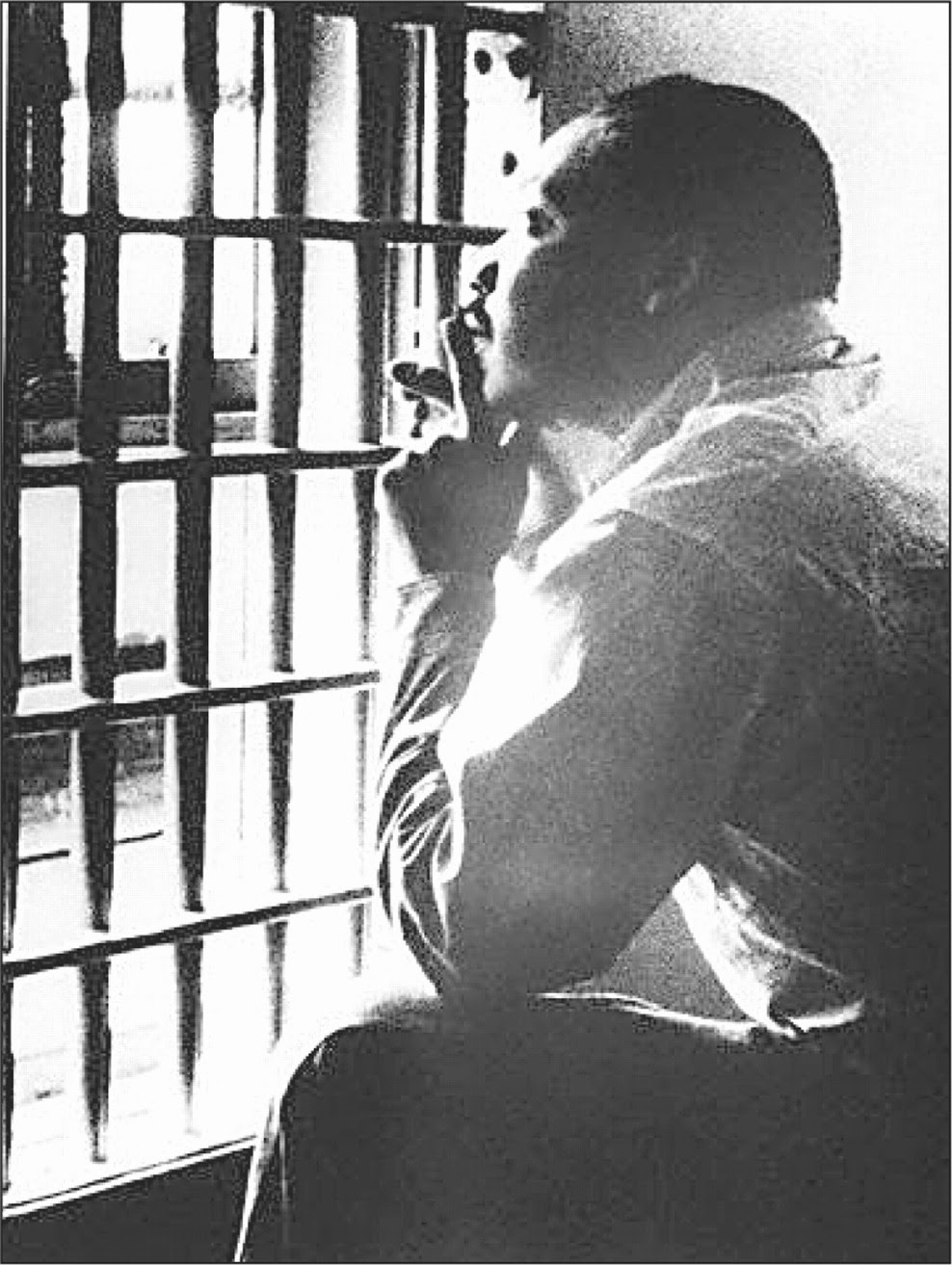

Mass

demonstrations and arrests soon followed.

Pretty soon, the infamous police dogs and fire hoses were loosed upon

the demonstrators. King, himself,

marched in defiance of the local authorities and shared a prison cell with his

fellow marchers. King proceeded to

pen a letter explaining his breaking of the law banning the demonstrators from

marching as well as explain to the white ministers who opposed his direct

action campaign why he could not follow their counsel to “wait” for justice.

“Letter

from Birmingham Jail” is a logical and philosophical masterpiece of persuasive

writing and is profoundly rooted in the traditions and thinkers of Western

civilization. King writes that

blacks “have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and

God-given rights.” He starts by

appealing to the pathos of the readers recounting many terrible injustices

suffered by southern blacks from the “stinging darts of segregation.”

King

addressed the fact that people were legitimately concerned that King and other

leaders were breaking the law “since we so diligently urge people to obey the

Supreme Court’s decision of 1954 outlawing segregation in the public schools [Brown v. Board of Education].

How can King advocate breaking some laws and obeying others? His answer is that “there fire two

types of laws: just and unjust.”

King is a firm advocate of the moral responsibility of obeying just laws

for order in civil society.

However, he argues that, “One has a moral responsibility to disobey

unjust laws.” He then quotes the great Christian

authority, St. Augustine, that “an unjust law is no law at all.”

Like

a good philosopher King sets about defining his terms “just” and “unjust” to

prove his case about following them.

A just law, King writes, is a “man-made code that squares with the moral

law or the law of God.” The unjust

is “out of harmony with the moral law.”

King assumes, like the Founding Fathers, that there was a natural law of

right and wrong given to humans by the Creator. For support for this natural law philosophy, King refers to

the great Christian philosopher of the Middle Ages, St. Thomas Aquinas, who

held that an unjust law is “’a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and

natural law.’”

King

provides further elaboration by positing that just laws uplift the human person

while unjust laws “distort the soul.”

Just laws are rooted in human equality as in the words of the

Declaration of Independence (“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all

men are created equal”), while unjust laws give a false sense of superiority

and inferiority. King uses the

terminology of the Jewish philosopher, Martin Buber, arguing that unjust laws

are based upon an “I-It” relationship rather than an “I-Thou,” treating people

as things rather than persons with dignity. In language that might seem out of place in today’s

politics, King went so far as to say that segregation was not only

“politically, economically, and sociologically unsound; it is morally wrong and

awful.” Indeed, he writes that

segregation is an example of man’s “terrible sinfulness.” Finally, the unjust segregation laws

were inflicted upon a minority with no vote in creating the laws and thereby

passed without consent, violating American principles of republican

self-government. He quotes from

St. Paul, Martin Luther, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln to support the

ideal of justice.

King

rejects the argument that his belief in breaking unjust laws would lead to

anarchy. “One who breaks an unjust

law must do so openly, lovingly, and with a willingness to accept the penalty,”

he writes. “I

submit that an individual who breaks a law that conscience tells him is unjust

and who willingly accepts the penalty of imprisonment in order to arouse the

conscience of the community over its injustice, is in reality expressing the

highest respect for law.” He

refers to other examples of those who were persecuted for disobeying the laws

of the state including Socrates, Jesus, the Christian martyrs, and the members

of the Boston Tea Party.

Martin

Luther King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” was a document that argued for justice

deeply rooted in the Western and American traditions. King agrees with James Madison, who wrote in Federalist #51 that, “Justice is the end

of government. It is the end of

civil society. It ever has been

and ever will be pursued until it be obtained.” In a state where the strong majority oppressed the weak

minority, “anarchy may as truly be said to reign.”

King

anchored the Civil Rights movement in American principles of liberty and

self-government. “One day,” King

wrote, the world will note that the Civil Rights demonstrators were “standing

up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our

Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells

of democracy which were dug deep by the founding fathers in their formulation

of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.”

__________________________________________

Tony Williams is the Program Director

of the WJMI and the author of four books including America’s Beginnings: The Dramatic

Events that Shaped a Nation’s Character.

1 comment:

Reading this helped make my celebration of Martin Luther King Day even more meaningful. Many thanks.

Post a Comment